The author is a freelance writer from Bozeman, Mont., and has her own communications business, Cowpunch Creative.

Second son, Blaine Hitzfield, manages marketing and distribution for his family’s farm. He notes nearly 80 to 90 percent of their products are sold direct to their over 4,000 customers via metropolitan buying clubs, online sales and their on-farm store.

According to Hitzfield, one of the advantages of stacking livestock enterprises is the scalability this production model provides. An element of scale is necessary for a business to be sustainable.

“In the commodity system, there is such a barrier to entry because of size,” says Hitzfield. “For example, if you are in the dairy business and you have a couple thousand cows, it doesn’t mean you are going to make money.”

Stacking livestock enterprises by raising multiple species on the same land base allows forage-based operations to vertically scale, explains Hitzfield, avoiding the size barrier commodity producers face altogether. His family started with grass-fed beef as their first livestock enterprise in the late 1990s, eventually adding pastured laying hens (seven years later) and pastured pork (10 years later) to the mix of their product offerings at the request of their growing customer base. Seven Sons has since diversified to even more species, including bison and lamb.

Strive for fast turnover

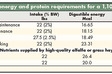

On the economic side, the value added from multiple enterprises mounts up swiftly, notes Hitzfield. In Seven Sons’ situation, grass-fed beef yields an estimated annual net profit of $620 per acre, pastured hogs pencil out at $810 per acre and pastured laying hens return $3,000 per acre.

Hitzfield recommends when selecting livestock enterprises to add-on to existing ones, consider choosing enterprises that are more easily scaled with a quick turnover. For example, adding pastured layers to a grass-fed beef or lamb operation. Shorter production cycles will mean a faster profit turnover.

Along with production and turnover cycles, another consideration, says Hitzfield, is seasonal availability of products marketed from each species. If customers want to buy a particular product such as grass-fed beef year-round, a means to store product will come in handy in the long run. Additionally, he stresses that with pastured products, farmers need to realize they are selling a completely different product than what goes into the commodity market.

“Things really changed for us the day we realized we were still trying to market our products like they were for the commodity market,” says Hitzfield. “At first, we didn’t have a vision for direct marketing when we got into pastured beef.”

While the value added by stacking livestock enterprises is quite obvious, there are many behind-the-scenes dynamics that go into making this model work successfully, such as production components and learning challenges. However, the final and most important key to running a profitable stacked livestock enterprise model, Hitzfield explains, is the marketing.

“Allan Nation says the highest return for pure knowledge is, has been and always will be marketing,” comments Hitzfield. “It’s the last and final step of getting further up the value chain and determines the return we get for the hard work and effort we put in.

“With pastured-based products, half the job is already done,” says Hitzfield. “We have a product that’s already in high demand. However, we knew if we were going to produce a quality product, we needed to find a customer base that appreciated that quality.”

Connecting with customers

When it comes to marketing, Hitzfield emphasizes the challenge farmers, and more specifically, direct marketers, face is inconvenience. Farmers sometimes forget how inconvenient they are just by the very nature of what they do (farming). Farms are located outside cities, miles away from populated areas. They are not very visible or accessible to the passerby.

Seven Sons’ marketing strategy takes the inconvenience barrier and turns it on its head. Instead of seeking out customers, the farm has taken a different approach by positioning the farm to be more accessible and easily found by customers both online and in the real world.

Hitzfield bases the farm’s online marketing around their website. He uses social media and e-newsletters to share content and drive traffic back to the website. He’s found having a strategy is the key to using time wisely and involves sticking to a schedule, figuring out what works and what doesn’t, and integrating networks when possible. Combined with the creation of metropolitan buying clubs (now spanning five Midwest states) and the already existing on-farm store, Seven Sons Farm has been able to successfully expand the accessibility of their pastured products, making it easier than ever before to get them in the hands of their customers.

Learn more about Seven Sons Farm on their website, https://sevensons.net.

This article appeared in the February 2016 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 26.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.