The decision to purchase forage can be easy when stocks are low and forage availability is scarce. Under this scenario, the decision relies on purchasing whatever is available. When not so urgent, or when we have options to choose from, more opportunities exist to be selective and choose the forage that best meets our needs. One of the first decision forks in the road is between grasses and legumes.

To compare grasses and legumes, we need to understand the distinction between cell contents and cell walls. Cell contents are nonfibrous components of the plant cells and include proteins, sugars, starches, lipids, and some minerals. Conversely, cell walls are fibrous components of the plant cells and mainly include pectin, hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. As they protect and give support to plant cells, these fibrous components contain very stable structures. The stability of these structures depends on the composition of the cell wall, mainly the degree and type of lignification.

Cell contents are typically completely and uniformly digested, while the digestion of cell walls is typically incomplete and nonuniform. Think about the digestibility of 1 ounce of sugar and the digestibility of 1 ounce of wheat straw.

In both cases, there is the same mass. Despite this, you probably already know that more energy will be obtained from the sugar than from the wheat straw. The reason is simple — sugar is mainly a cell content component of almost complete and uniform digestibility (let’s say 98 percent digestibility), and wheat straw is mainly a fibrous cell wall component of incomplete and nonuniform digestibility (let’s say 30 percent digestibility). So, as the forage contains more cell contents, the digestibility will trend toward 98 percent, and as the forage contains more cell walls, or fiber, the digestibility will trend toward 30 percent.

Maturity matters

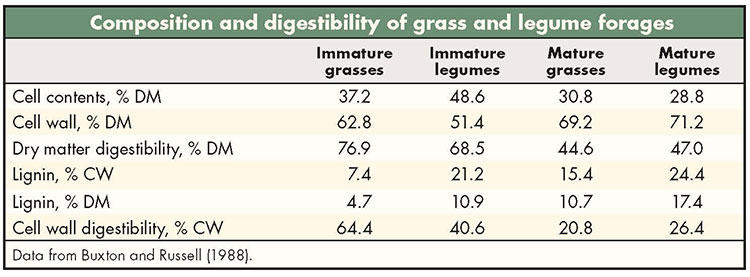

With this background information in mind, we are now ready to understand that, on a percent dry matter basis, legumes typically have more cell contents and less cell walls than grasses (see table). This means that the dry matter digestibility of legumes such as alfalfa is typically greater than the dry matter digestibility of the grasses.

One concept that frequently generates confusion is the quality of the cell walls, which is commonly described by the degree of lignification. In general terms, the cell walls of legumes are more lignified, on a percent of cell wall basis, than the cell walls of grasses (see table). For this reason, certain grasses, such as ryegrass at vegetative stages, can have very high dry matter and cell wall digestibilities.

One concept that frequently generates confusion is the quality of the cell walls, which is commonly described by the degree of lignification. In general terms, the cell walls of legumes are more lignified, on a percent of cell wall basis, than the cell walls of grasses (see table). For this reason, certain grasses, such as ryegrass at vegetative stages, can have very high dry matter and cell wall digestibilities.

Obviously, a greater lignification of the cell wall will lower the digestibility of the fiber. However, a greater lignification of the cell wall does not necessarily mean the digestibility of the forage, on a percent dry matter basis, will be lower, too. Remember, legumes can still have much greater cell contents of complete and uniform digestibility than grasses, making the forage more digestible.

Another concept to consider when comparing grasses and legumes is the drop of quality with maturity. As mentioned before, grasses can have very high dry matter and cell wall digestibility at vegetative stages. However, as maturity advances, the digestibility of the cell wall declines very fast. This reduced cell wall digestibility is much faster for grasses than for legumes (see table). For this reason, managing grasses can be more challenging than managing legumes when climatic conditions, such as frequent rainfall, are not optimum for harvesting hay. Pasture grasses that are grazed in a vegetative state can be extremely high in digestibility.

When comparing forages, do not just look at the cell wall or fiber digestibility. Even though cell wall lignification is very important, look at other aspects of forage quality as well, including cell contents or fiber.

When comparing grasses to legumes, some general conclusions are: 1) legumes typically have lower concentrations of cell wall than grasses, on a percent dry matter basis, therefore being more digestible, 2) the cell walls of legumes are typically more lignified, on a percent of cell wall basis, than the cell walls of grasses, which translates in lower cell wall or fiber digestibilities, and 3) the decline in cell wall digestibility, on a percent of cell wall basis, with advancing maturity is much greater for grasses than for legumes.

I emphasized several times whether we are referring to a percent dry matter basis or a percent of cell wall basis. Similar to comparing pears to apples, understanding that these terms are different is critical when comparing forages.

This article appeared in the August/September 2017 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 24.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine