As a hay industry, there are still a number of hay sales that occur “by the bale.” Yes, it’s easier, but if the sale is made without factoring in bale weight and moisture, there’s a good chance the buyer is paying either too much or not enough.

You’ve probably heard this issue reiterated many times over the years, but it’s a safe bet that you’ve never heard it when the price of hay is as high as current values.

For a large swath of the western U.S., drought was the dominating factor during the past growing season. Many livestock producers know they will be short on winter hay or will cut it pretty close. Accurate inventories will no doubt mean the difference between having enough hay or having hungry, low-performing cattle.

My point is that known, accurate bale weights have always been important, but they’ve never carried the degree of economic significance as this year. It’s true whether you’re selling or buying hay or feeding your own.

Reasons abound

There are a number of factors that can explain why two or more bales of equal size can have drastically different weights. These include:

• Bale density

• Bale moisture

• Time of sale

• Forage species (grass or legume)

• Forage maturity (percent leaves and stems)

• Model and age of the baler

It’s fairly intuitive that the size of a bale will impact bale weight, but what may be overlooked is the degree of change that occurs when a bale is only 1 foot wider or 1 foot greater in diameter. The latter accounts for the largest change.

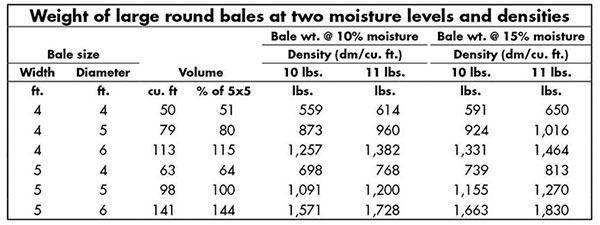

A bale that is 4 feet wide by 5 feet in diameter (4x5) has 80% of the volume of a 5x5 bale (see table). However, a 5x4 bale has only 64% of the volume of a 5x5 bale. Those percentages also translate to differences in weight if all other factors are equal.

Bale density, which typically ranges from 9 to 12 pounds per cubic foot, also plays a rather large role in final bale weight. In a 5x5 bale, the difference between 10 and 11 pounds of dry matter per square foot amounts to over 100 pounds per bale at both the 10% and 15% moisture levels. Missing the weight of a bale by 10% amounts to some pretty significant dollars when multiple tons are being purchased.

Forage moisture also plays a role in bale weight but to a lesser degree than bale density unless bales are extremely dry or wet. Wrapped bales, for example, can vary in moisture from 30% to over 60%. When purchasing baleage, it is always recommended to either weigh the bales or have a rock-solid moisture test.

Time of purchase impacts bale weight in two ways. First, if you’re purchasing bales out of field, they are likely going to be at a higher moisture level and weight than they will be after being cured in storage. There is also a natural tendency for dry matter loss during storage that the buyer will incur if bales are purchased immediately after baling. As has been well documented by research, storage losses can range from below 5% to over 50%, depending on storage method.

Forage species can also come into play. Grass bales generally will weigh less than legume-based bales of similar size. This is because legumes such as alfalfa will make a denser bale than a grass species. In one Wisconsin study, the average weight of a 4x5 legume bale was 986 pounds. This compared to 846 pounds for grass bales of the same size.

Plant maturity impacts bale density and ultimately bale weight. Leaves generally pack better than stems, so as plants mature and develop a higher percentage of stems to leaves, bales generally become less dense and weigh less.

Finally, there are many models of balers of differing ages. This variation, coupled with operator experience, lends further variability into the bale density and weight discussion. Newer machines are able to make a much denser bale than most older ones.

Given the number of variables that determine the actual bale weight, buying and selling large round bales based on a weight guess is likely going to result in a transaction that is either above or below the already high market values of today. This can be extremely expensive for the buyer or seller, especially when a large number of tons are purchased over a period of time.

Weighing round bales might not be as convenient as not weighing them, but there are very few situations where a bale weight isn’t attainable. Take the time to weigh bales (all or a few), regardless of size or shape, whenever a transaction is made. Also, don’t guess when making inventory estimates of your own hay. That, too, could be an expensive error come next spring.