The author is an extension beef specialist with the University of Kentucky.

Many of us use the weather as an ice breaker to start a discussion. This is partly due to the fact that the farming community is directly impacted by when the first and last frosts will occur as well as the frequency and amount of rain that falls across the agricultural landscape.

The weather is so important to our daily lives that the national news dedicates air time to cover local weather; there are even stations that only cover weather-related stories. Technology has put up-to-date weather information in the palm of our hands through apps on our smartphones.

Much of the United States remains in the grip of dry conditions. Upon writing this column, the Drought Monitor Map released on November 27 showed 74% of the United States being listed in the abnormally dry through exceptional drought categories, with 41% of the country experiencing some degree of drought. This was similar to the fall of 2022 in which more than 75% of the United States was experiencing dry conditions. Areas most affected by low precipitation last fall were in the Upper Plains states and the Midwest. The East Coast was also shown as being very dry.

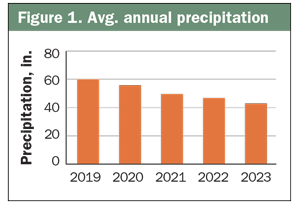

I also took a look at the precipitation data from the Kentucky Mesonet website spanning 2019 through 2023. Any weather sites with incomplete precipitation data were removed from the data set. The number of weather collection stations included in the data set ranged between 66 in 2019 to 75 for 2023.

As shown in Figure 1, average annual precipitation has declined over this five-year period. The annual precipitation received in 2023 was 16 inches less than in 2019, which is approximately a 25% reduction. This information simply illustrates annual precipitation has been less in recent years, leading to challenges in managing pastures as these dry conditions can impact forage production and persistence.

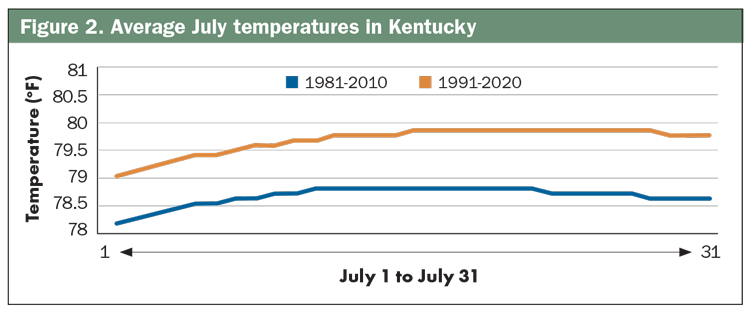

On the other hand, temperatures seem to be climbing some, but when looking at the data, it appears to be a small spike of around 1ºF on average. Figure 2 compares the average July temperatures for the Bluegrass State for the time frames between 1981 through 2010 and 1991 through 2020. The trend suggests slightly warmer summer temperatures. As most pastures in the area are dominated by cool-season species, though, warming during the summer months may have a greater impact on production of these forages. Combine warmer temperatures and less precipitation and one can expect changes to occur in our cool-season pastures.

Warm-season encroachment

For several years we have noticed common bermudagrass encroachment in the southern edge of Kentucky. This past year, I was on a few farms in southeast Kentucky where dallisgrass was found in the fields. Johnsongrass has also been a burden for our alfalfa producers, and it seems to be becoming more prevalent. Given these trends in warm-season forage growth, this past summer, Katie VanValin with the University of Kentucky and our crew looked at the issue a bit closer.

We visited seven farms across the state to collect botanical composition data. Using a grid sampling approach, we estimated botanical composition for 18 fields on these farms. Since tall fescue is the dominant forage in our pasture systems, I did a quick tally for just tall fescue. The lowest percentage of tall fescue in a field was 5%, and the highest prevalence was 94%.

Interestingly, the average percentage of tall fescue for the fields was only 62%, while the median was 76%. Clearly, we were not dealing with straight tall fescue pastures; however, it is too early to get a deeper look into this information. Intentional practices, such as interseeding clover, may have contributed to some of this difference in stand composition. However, we need to appreciate the diversity of plant species in our pasture systems and that this diversity may be changing over time.

As we move forward in stewarding our grazing systems, keeping an eye on botanical composition changes will be of value. The more information we have on what species are in our pastures, the better we can manage forage production.

Change is not always bad. Many of our warm-season forages are high in quality and provide growth when our cool-season forages are not as productive. However, loss of desirable forages to unpalatable or toxic plants as a result of overgrazing during drought conditions is not ideal. Take the time to learn how to assess your pastures for cover and botanical composition. Monitor your grazing areas and note the changes that are occurring. Then develop a plan to encourage this shift or change the course if undesirables are encroaching. Happy grazing!

This article appeared in the February 2025 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 10-11.

Not a subscriber?Click to get the print magazine.