A mystery & reality |

| By Chet Loveland |

|

frosted alfafa |

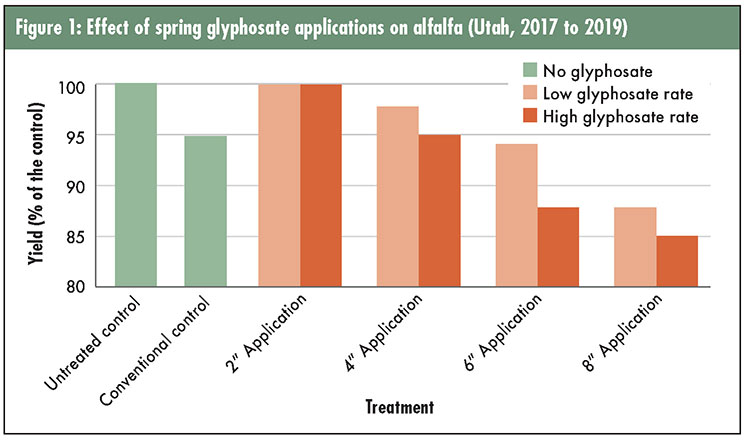

The author is a graduate research assistant at Utah State University in Logan. Researchers are still trying to find answers to why alfalfa injury occurs when glyphosate is applied and then followed by a spring front event. Herbicide-tolerant crops have been widely adopted across production agriculture. Over 90% of canola, sugar beet, soybean, cotton, and corn crops in the U.S. are herbicide tolerant. Most prominent among herbicide-tolerant crops are glyphosate-resistant (GR) varieties and hybrids. GR alfalfa has also become widely used in recent years, although adopted at a slower pace than other crops due to its perennial nature. Despite the higher seed cost of GR alfalfa, the majority of users (72%) report that they would plant it again. Growers have embraced the technology because it provides simple, effective weed control. Alternative conventional herbicides often limit growers to specific application timings and, even when a proper application is made, the crop may still be subject to some degree of injury and/or stand loss. As time has allowed us to observe GR alfalfa use across the country, many of its initial selling points have held true. However, an important exception to the rule occurred when crop injury was observed following a glyphosate application in California in the spring of 2014. Since then, apparent glyphosate injury has been documented in the intermountain regions of California, Oregon, and Utah. This raised the question: Is GR alfalfa truly immune to glyphosate applications, or does crop injury result just as it does with conventional herbicides? A tie to spring frosts More than 30 studies have been conducted to determine the source of this injury and identify ways to help growers mitigate their risk of crop injury and yield loss. As these studies were compared to one another, a pattern of conditions emerged for which injury is contingent upon. Most importantly, injury only occurred in environments prone to spring frosts. For injury to occur, both a glyphosate application and a frost event were needed to have taken place within a similar time frame. Thus, when the term glyphosate injury is used, this does not imply glyphosate as the source of injury; the mechanism behind this injury is still not fully understood. Rather, the term is used to distinguish this injury from other forms of injury. Glyphosate injury is sporadic, affecting plant stems at random instead of impacting the entire crop uniformly. Plants usually expressed this injury as chlorosis (yellowing) and stunting. These symptoms persisted until the first cutting, as some chlorotic plants turned necrotic (brown). Stunting continued to persist as well, impacting yields. Fortunately, the impacts of this injury were isolated to the first crop. No stand loss has been observed, indicating that plant population is not affected by this injury. Notably, no residual injury or yield loss has occurred in the following cuttings, regardless of the degree of damage incurred during the first crop. After first cutting, affected plants recovered, showing no lingering effects of glyphosate injury. To better understand how glyphosate was impacting GR alfalfa, a few questions needed to be answered: Do higher glyphosate rates result in greater injury? Does the timing of glyphosate applications play a role in injury? How does glyphosate injury compare to injury from conventional herbicides? Injury varied In our Utah trials that have been conducted during the past three years, 10 treatments were imposed. The control was an untreated check, regarded as the standard for yield in a crop with no injury. The second treatment was a mix of metribuzin and paraquat. This was applied at dormancy as a comparison for typical conventional herbicide injury and is referred to as the conventional control. The remaining eight treatments received applications of glyphosate at two different rates and four plant growth stages. The two rates were a low and a high rate (Roundup PowerMAX at 22 ounces [oz.] per acre or 44 oz. per acre). The applications were timed at 2-inch intervals, occurring at 2, 4, 6, and 8 inches tall. Alfalfa that received a glyphosate application at 4 inches or greater generally exhibited more injury symptoms than alfalfa exposed to conventional herbicides. It also seemed that a high glyphosate rate resulted in greater injury expression. So, as a rule, injury expression was greater as glyphosate rate or crop height at application increased. Of course, with some forms of injury this does not mean that all is lost; many crops recover from apparent injury before harvest, having no reduction in yield. However, in the case of glyphosate injury, crop injury often translated into yield reduction. Figure 1 illustrates the impact various treatments had on yield. In general, yield reduction was greater when high glyphosate rates were used, as well as when glyphosate applications were made at taller growth stages.  When a high rate was applied at an 8-inch growth stage, yields suffered an average reduction of 15%, or about 0.3 to 0.4 tons per acre. The greatest yield reduction was 0.8 tons per acre. Using a low rate at this same growth stage, average yield loss typically ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 tons per acre with the worst-case reduction being 0.7 tons per acre. An unexpected lesson learned was that older alfalfa stands had a tendency to show greater injury symptoms and yield reductions than younger stands. Many contributing factors could be the cause of this. Older stands lack the vigor of younger stands; furthermore, thinner plant densities enable greater glyphosate plant coverage than would occur in a thicker, younger stand. Regardless of the reason, as a stand ages it will grow ever more susceptible to the effects of glyphosate injury. Mitigation strategies So, what can be done to prevent or reduce the impact of glyphosate injury?

Moving forward Although effective mitigation practices have been established, the mechanism behind the injury remains elusive. Is this injury, in fact, a form of frost injury that has been intensified through glyphosate application? Or perhaps is the effectiveness of the glyphosate-resistant trait diminished by frost events? A seemingly endless number of biological and ecological factors may play into this injury as well, and any one of them could be the key to better understanding and preventing this injury. Moving forward, researchers will seek to find answers to these and other questions. This article appeared in the March 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 24 and 25. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |