Wet years have favored weeds |

| By Melissa Bravo |

|

|

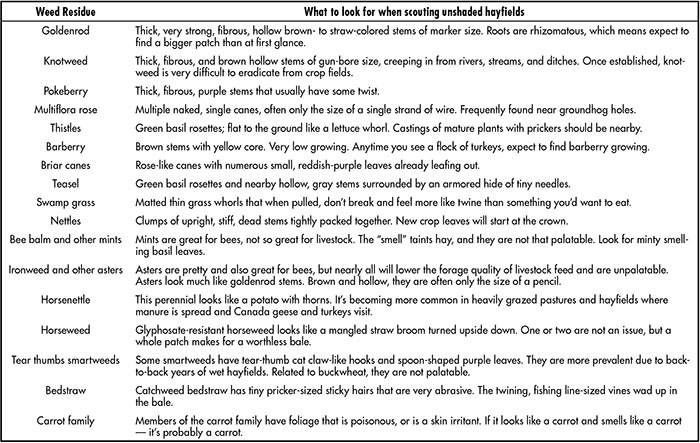

Here we go again. Another mild winter of heave and thaw with little snow cover to protect the shallow roots and crowns of improved forage crops. Without that snow barrier, species such as alfalfa and timothy — the most susceptible of our non-native forages — are subject to winter injury, which thins stands. This leaves less competition for weeds to establish and flourish. Learning some skills to evaluate stand composition before you harvest first-cutting hay can add to profitability, but you must first be able to identify problem hayfield and pasture weeds. During the dead of winter, most fields look uniformly brown. Then, as temperatures begin to warm, they look uniformly green. The problem is that sometimes “green” may consist of more than just desired forage species. Weeds can contribute to yield, but they also can often lower the quality and marketability of hay, especially if harvest is delayed by rain. Plan to spend an hour in each field scouting before you get the mower out. Place a value on your time so you can validate the cost to your hay customers. If control measures are required, those costs need to be captured as well. A thorny issue Weeds establish in hayfields and pastures through various mechanisms and events. Manure spreading is one way that we often think about in terms of introducing new weed seeds. However, another less thought of carrier of weed seeds is birds. If birds can roost along field edges, expect to find woody canes of honeysuckle, autumn olive, multiflora rose, wild blackberry brambles, pasture rose, privet, and Japanese barberry coming up as far into the field as the branches extend. All except honeysuckles have thorns that are capable of damaging an animal’s tongue and gums. Also look for smilax vines (green briars), and to a lesser extent bur cucumber and wild cucumber. Field edges are also an area where large branches of emerald ash borer-damaged limbs or even entire ash trees (sometimes with barbwire attached) have fallen into the field and need to be removed. Grazing animals use teeth, tongues, and lips to pull grass swards into their mouths, and cud chewers will mash that feed into a pulp. Woody thorns will greatly reduce feed efficiency and feed intake of an otherwise unblemished hay bale. Remember, too, that baleage ferments the carbohydrates in plant material, but it’s not going to soften up damaging thorns. Pregnant heifers and cows can lose condition having to pick through hay to find a mouthful that does not have thorns. Livestock can get a pus-filled soft tissue infection called wooden tongue as a result of an Actinobacillosis bacterial infection. Oral thorn injuries can lead to an inability to eat or drink for several days, drooling saliva, rapid loss of condition, a painful swollen tongue, and mouth nodules and ulcers. Also recognize that young stock only have baby teeth, and they can’t masticate a woody stem like an adult animal. Check those bare spots Evaluate bare ground areas for weeds that like full sun. Table 1 lists those weeds that can greatly impact hay quality. Here’s how you identify these when the desirable grass swath is still brown. Step 1. Train your eyes to see the color and texture of desired grasses. For example, dead orchardgrass feels, looks, and grows differently than reed canarygrass, timothy, smooth bromegrass, and bluegrass castings. You can usually find mature grasses with seedheads still attached on field edges for accurate comparison. Step 2. Get down on one knee and look closely at any bare ground spots. Look for foliar patches of brown-gray and off-white that don’t match desirable species. Step 3. Take note of anything green, especially if it is flat and spread out low to the ground. These are most likely winter annuals and biennial weeds that have cropped up since last year’s final cutting. Finally, look carefully for single stem thorny canes.  Weed control options Depending on what the producer wants and the degree of infestation, I often mark areas that need control measures with colored ribbon or paint. You might be surprised, but I suggest leaving the dandelions for the bees. They are high in protein and are not going to impact forage quality. Oftentimes, I will take a tree-spade shovel or backpack sprayer and treat as I scout. I also pick up any metal cans or trash that I see. Spading is especially effective for musk thistle, bull thistle, and beginning perennial patches of spreading Canada thistle roots. For severe weed encroachment situations, tillage or broadcast spraying will be needed. Expect the average cost of a growth regulator herbicide applied at 2 quarts per acre to be around $30 per acre plus the application cost. Growth regulator herbicides include Garlon, 2,4-D, Banvel, clopyralid, Milestone, and triclopyr products. Edge spraying can be done with just one section of a sprayer boom (30 to 40 feet), so make sure you calculate only that width when the load is mixed. Use a broad-spectrum woody herbicide along hedgerows, which will mean sacrificing any legumes in the swath. You can no-till legumes back in after the harvest or grazing restriction window has passed; this may range from seven days to 20 months, depending on the chosen product. Read the herbicide label and plan ahead. Spray with a crop oil carrier when shrubs have just begun to leaf out but before the hay crop is mowing height. Excessive rainfall in back-to-back years has caused a lot of poor-quality hay to be made. It has also brought on a flush of perennial and annual weeds. This spring will be a good time to evaluate current hayfields and pastures and take appropriate action to get this new flush of weeds under control while also improving forage quality.  Melissa Bravo The author is an agronomic and livestock management consultant based in Wellsboro, Pa.

|