Dewing it the small way |

| By Mike Rankin, Managing Editor |

|

Bales Hay in Buckeye, Ariz., is one of the first farms in the U.S. to adopt steaming technology for small bales. |

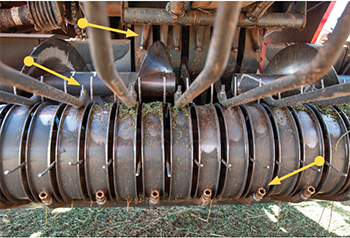

Bales Hay in Buckeye, Ariz., is one of the first farms in the U.S. to adopt steaming technology for small bales. One-pass hay steamer technology is nothing new to Western haymakers, at least those who make and market large square bales. But what about hay operations that fight the same arid conditions and make the 90- to 100-pound three-tie bales or lighter two-tie bales? Their options have been limited . . . until now. Bales Hay is a family-run operation near Buckeye, Ariz., just southwest of the Phoenix metro. Steve Bales, his son, Trevor, and cousin Brian Turner form a trio that farms over 2,000 acres of owned and leased land, consisting mostly of flood-irrigated alfalfa. They sell much of their hay direct-to-consumer or to retail outlets. Horse owners make up a large part of their clientele. “We need our hay to be nutritious, but it’s also essential that it be visually appealing,” Trevor noted. “Our hay has to retain leaves and look good or our customers won’t buy it, regardless of how it tests.” In the past few years, Trevor’s reputation as a haymaker has spread beyond the Arizona desert. In fact, he’s become somewhat of a social media sensation with postings on Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook. It’s through these channels that Trevor brings the hayfield to living rooms throughout the world. It’s also how Bales Hay Sales became one of the first operations in the U.S. to test drive the Staheli West DewPoint 331 hay steamer for small square bales. Staheli West, based in Cedar City, Utah, had been manufacturing its larger DewPoint 6210 machine for over 10 years but was in the later development stages of testing a smaller, less expensive version for small square balers. “On social media, I’ve noticed how everyone just highlights their best products and successes,” Trevor said. “Last year, I decided to point out that we’re no different than everybody else, and there are times that we have to bale when the hay is too dry, and we lose too many leaves. I demonstrated what I was talking about and mentioned that it sure would be nice if Staheli West would send a steamer our way to use. Then, two or three days later, I got a phone call from the company, and they wanted to send us a steamer to demo.” Testing the water The company sent down a kit for a baler, and arrangements were made for the use of a larger tractor because none of Bales’ had enough horsepower (HP) to pull and operate the steamer and baler train. The DewPoint 331 remained on the farm for about a week, then came the difficult task of decision-making. “Of course, I thought it was cool, but at that point, I really put it on our field manager, Brian, to crunch the numbers and make any kind of final decision,” Trevor explained. “I told him it was up to him 100%. I would have been happy if we decided to run four power takeoff (PTO) balers or two steamers.” This proved to be a tough decision on several levels. First, only one steamer wouldn’t work. It had to be two or none. “Our baling window isn’t wide enough for one steamer, and if that steamer breaks down, then you still have to keep three or four balers as backup,” Trevor said. In addition, the Bales crew would also need to purchase two larger tractors to pull the steamer and the baler. The minimum power needed on their flat, desert ground was 125 HP.  Steam is transferred to the baler through hoses. It’s then applied to the windrow as it enters the baler via three manifolds (see arrows). The amount of steam coming through each manifold is controlled by the operator. On the plus side was a wider window for baling in the arid desert environment. During the extreme heat of mid-summer, they still wouldn’t be able to bale all day, but they could bale during the otherwise dewless nights and into mid-morning. Running two steamers would also mean a reduction in labor. “Finding good labor is becoming more difficult, and with the steamers, we only need two baler drivers instead of four or five,” Trevor noted. It took several months for Brian to make a final decision. Weighing heavily into the decision was the fact that the farm had four motorized balers that were near the end of their useful life and would soon have to be replaced, steamers or not. Also, two of their current baler tractors needed to be upgraded. The question boiled down to if the farm would run four new PTO-driven balers or two new balers with steamers. “It would have been a harder decision to make if some of our current equipment didn’t need to be replaced,” Trevor asserted. Ultimately, Brian recommended the operation bale with two steamers. “There are a lot of farms making big square bales that have been using steamers with good success, so that made the decision a little easier,” Trevor said. “It wasn’t like we were going to be the first. The only difference is that we make small square bales.” Trevor, Brian, and two employees attended a school this past year in Utah for those who had purchased a steamer. “They did a really good job of showing you how to troubleshoot the machine,” Trevor said. “They also thoroughly go over the owner’s manual with you.” Up and running The two DewPoint 331s arrived on the farm in early May. The Bales ultimately settled on two, 140 HP Fendt tractors to power the baling train. They wanted a little more horsepower than the minimum recommended for their conditions. The farm uses a 5,000-gallon storage tank for water. For every 3 gallons of salty, desert water that goes through the water system, only 1 gallon of clean water is generated. The other 2 gallons of salty water are used for dust control on the farmstead. The steamers, loaded with over 600 gallons of water, are heavy, weighing about 8 tons. For that reason, the units have their own set of trailer brakes. Comprised with what is essentially a low-pressure boiler (about 15 pounds per square inch), the DewPoints are equipped with numerous safety features. The steamers will operate from three to five hours before needing to be refilled with water. Operational time depends on the amount of steam being released through the manifolds on the baler. Steam is applied to the hay windrow as it is picked up by the baler. The three separate manifolds are located below the pickup, above the pickup, and in the bale feed and packing chamber. The operator has full control as to the amount and percent of steam being released among the manifolds. For example, if the top of the windrow is still wet from dew but the bottom is dry, the top manifold can be shut off or reduced, and steam is only applied to the drier bottom. The interactive touchscreen in the tractor cab makes the adjustments relatively simple and fast. Out of the baler, the steamed bales are still hot. In fact, it’s recommended that they not be accumulated and stacked for 30 minutes.  “One thing about the steamer is that it makes an awesome flake,” Trevor Bales said. Trevor (left) and Brian Turner routinely inspect bales once they cool in the field. “Nothing can beat natural dew, but those nights and mornings when it’s windy and there’s no dew, that’s when the payback comes,” said Trevor of their experience this summer. When there is dew, or if baling bermudagrass, the Bales still pull the steamers but just don’t generate any steam. “One thing about the steamer is that it makes an awesome flake,” Trevor noted. “When you cut the strings, those nice, uniform flakes just fall apart from each other but stay intact. Surprisingly, I get a lot of complaints about bales that don’t maintain a flake when they’re cut open. I think our customers will really notice a difference with the steamed bales,” he added. Deep steamer roots The current version of the DewPoint 331 has been in development for about four years. “Ironically, we originally started with a smaller version in the 1990s when Dave Staheli first invented the steamer,” explained Logan Staheli, who serves as the director of marketing for Staheli West. “When we decided to bring the units to market in 2009 and 2010, the big baler had become popular, and that is was what we were using on our farm. So, we came out with the big bale steamer.” Staheli West has been testing the DewPoint 331 for the past three years in Utah. In 2020, they released six units for beta testing. This year, the small steamer is in limited production status. By the end of the year, the company expects to have 40 operating units on 20 different farms. Next year, the unit will reach the full production stage. “There have been some minor issues with the small steamers since releasing them this year, but we are working really hard to get all the issues resolved so that we are ready to move into full production,” Staheli said. “We are confident that we have some pretty good solutions and updates that are going to fix the quirky bugs some of our customers are seeing. Luckily, we haven’t had any major issues that have shut our customers down for any extended period. Our customers really like them so far.” Included in that group is Bales Hay. “We’ve been happy so far; it does what it’s advertised to do — save leaves,” affirmed Brian when asked for his first-year assessment. This article appeared in the Aug/Sept 2021 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 22, 23 and 24. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |