Farmers and ranchers operate with the understanding that many things are beyond their control despite the best laid plans and management. Market prices, input costs, pests, and diseases are just some of the things that must be dealt with and adjusted for on an annual basis.

Then there is the weather and the short- and long-term factors that drive it. Forage production, both hay and pasture, is extremely sensitive to weather from both a yield and quality standpoint.

Most agriculturists are familiar with La Niña and El Niño, which are dictated by a relatively small portion of the ocean’s surface temperature. A cool surface favors a La Niña weather pattern, while a warmer water surface associates with weather conditions characterized by El Niño. Both offer extreme, but different, weather conditions.

“We’ve been locked into a La Niña weather pattern since 2020, and it has been historically long in duration and strength, but she’s just about done,” asserted Matt Makens while giving his annual weather update during the CattleFax Outlook Seminar at the Cattle Industry Convention in New Orleans, La., last week.

Makens is a meteorologist and atmospheric scientist with Makens Weather LLC based in Colorado. He said the extended La Niña was largely responsible for the long-lasting drought plaguing much of the West and Great Plains during these past several years.

“The impact of this La Niña has extended far beyond the U.S.,” Makens said. “We have also seen drought conditions in South America and Europe, but Mother Nature likes to keep things in balance, so Australia has actually seen a surplus of moisture.”

Exit door is open

Makens sees clues that La Niña is on her way out. The ocean conditions are warming up, he noted. Moisture conditions have already started to improve this winter in previously drought-stricken areas.

“By spring, our models suggest that a La Niña will only be about 14% likely, down from the current 60%,” Makens said. “That’s a rapid loss, and it’s already occurring.”

What does the loss of La Niña conditions mean?

Makens said there will be an extended period of time where we will be in a neutral phase. “Next fall, we begin to open the door and see if El Niño wants to come in,” Makens suggested. “At that time, the models suggest that the probability for an El Niño is about 52%. That’s not a slam dunk.”

The atmosphere doesn’t have to immediately follow the ocean conditions, according to Makens. It can sometimes take several months or seasons before the atmosphere adjusts to the oceanic temperature conditions. That means that this spring La Niña is still controlling the atmosphere.

“This summer we may have a neutral atmosphere before some El Niño elements begin to exist next fall,” the meteorologist said. “Remember how long it took to escape the 2011 and 2012 drought? We finally got out in 2017.”

Best-fit predictions

Makens looks at past years since 1950 to find situations that “best fit” the current situation, and then he adjusts accounting for current unique conditions.

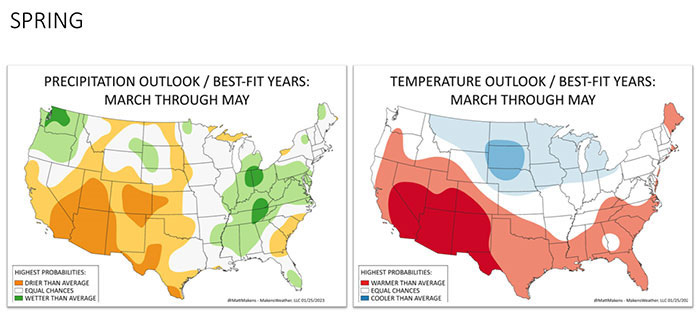

Based on five similar years, Makens offered his 2023 forecast using the analogs. For spring, he said the weather pattern still looks like one we’d see for La Niña. Dryness overspreads the Southwest again. The Northwest and Northern Plains will get “hit and miss” moisture. The Southern Plains will remain dry. Moisture will be favored in the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys.

Makens also is forecasting a cooler than average spring. The growing season will likely be delayed in some cases. It will be very warm across the Southwest, though.

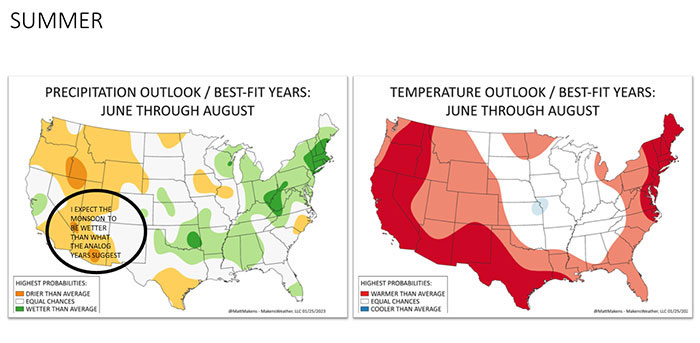

For summer, things begin to change, according to Makens. “I expect a more neutral-based forecast as the atmosphere begins to catch up with the ocean conditions,” he said. “This means we begin to eliminate the extremes of an El Niño or La Niña.”

Makens said his analog didn’t really predict as much of a monsoon in the Southwest as what he thinks we’ll have; this will take away some moisture from the Corn Belt. Overall, it should be a more favorable summer for moisture compared to the past several years.

Other than the Southwest, temperatures are expected to be neutral to cooler than average in pockets.

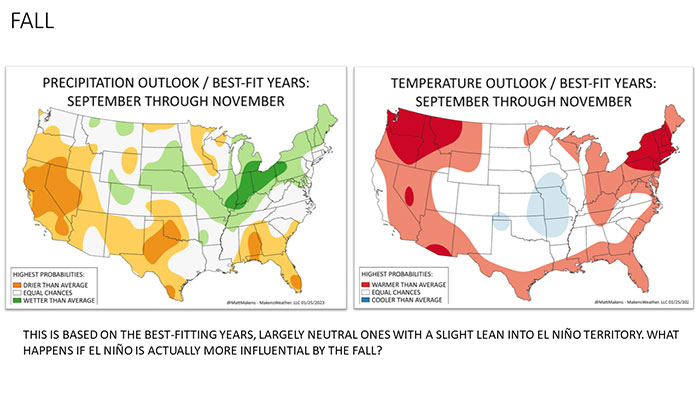

“There are two possibilities for fall based on the uncertainty of what El Niño might do,” Makens said. “The best-fit forecast spreads the moisture farther west. There will be a much more favorable precipitation forecast for states like Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska.”

Temperatures will look to be much more moderate than what was experienced this past fall.

Makens said that if El Niño kicks into high gear by this fall, expect a lot more rainfall than what a neutral fall might look like. “I think this is not likely to happen; it’s too quick of a transition,” he asserted. “El Niño will kick in, but give it some time.”