At last month’s International Silage Conference held in Gainesville, Fla., keynote speaker Kenneth Kalscheur kicked off the opening session with an overview of silage utilization in the U.S. Kalscheur, an animal scientist at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center, provided insight into the silage species, crop production, and feeding strategies that are common on our nation’s dairies while suggesting some areas of improvement.

Corn silage accounts for the lion’s share of silage production across the country because it provides a high-yield, high-energy forage that only requires one harvest. These management factors lend themselves to less labor and more consistent quality compared to other forages like alfalfa that are cut for silage multiple times per year. Even so, alfalfa is the second-most popular silage species in the U.S., and other grass forages are readily utilized in various regions depending on the climate, soil type, and growing conditions.

Kalscheur’s research has primarily focused on how to increase the amount of forage in dairy cow diets without sacrificing animal productivity. In other words, he has examined the best ways to take advantage of forage fiber and its contribution to energy intake, rumen function, and milk fat production without jeopardizing feed intake or milk output.

“It’s always about trying to optimize the amount of nutrients in the diet,” Kalscheur said about adding forage to dairy rations. “Yes, we can feed 100% forage. But we also know we can increase productivity from those animals if we can balance those diets for nutrients.”

Kalscheur added that including more forage fiber to lactating dairy cow diets also lowers total feed costs and supports the utilization of crops that are not in competition with human food, monogastric feed, or biofuel production. Overall, he contended that high-forage diets create healthier animals that produce more milk. But the key to reaping all of these benefits isn’t just adding more forage fiber to dairy rations — it’s about adding more highly digestible forage fiber.

Keen on quality

There are several strategies to enhance silage fiber digestibility. Kalscheur categorized these by physical treatments like chopping and kernel processing, biological treatments like enzymes and inoculants, chemical treatments like acid and hydrolyzing alkalis, and genetic treatments like brown midrib (BMR) corn silage and reduced-lignin alfalfa. Even though animal intake typically declines when forage is added to the diet, milk production doesn’t necessarily have to.

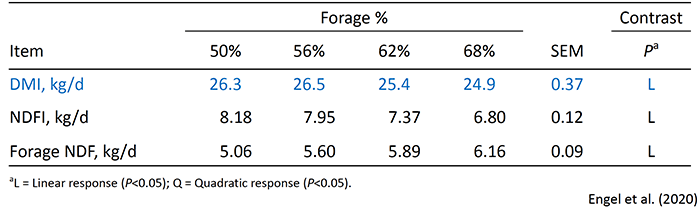

To demonstrate this, Kalscheur showed results of a study that compared dairy rations containing different amounts of high-quality forage. The control diet included 40% BMR corn silage and 10% third-cutting alfalfa silage. Then, researchers added higher quality alfalfa silage from fourth cutting in 6% increments on a dry matter basis to get treatments with 56%, 62%, and 68% total forage. All diets were balanced to have roughly 17% crude protein (CP) and 30% neutral detergent fiber (NDF).

As the amount of forage went up, dry matter intake went down, which was to be expected (Table 1). However, Kalscheur pointed out that since high-quality alfalfa silage was the added ingredient, milk production stayed relatively stable. Furthermore, cows consuming diets with greater fiber digestibility from more high-quality alfalfa silage had greater milkfat and better feed conversion efficiency, which is energy-corrected milk divided by dry matter intake.

“If we continue to add [high-quality forages] to diets, we see improvements in feed conversion efficiency every time, and our ability to convert silage to milk is what we are after,” Kalscheur said. “This is very positive; this is something we need to focus on to convert silage to milk and meat.”

Extreme processing

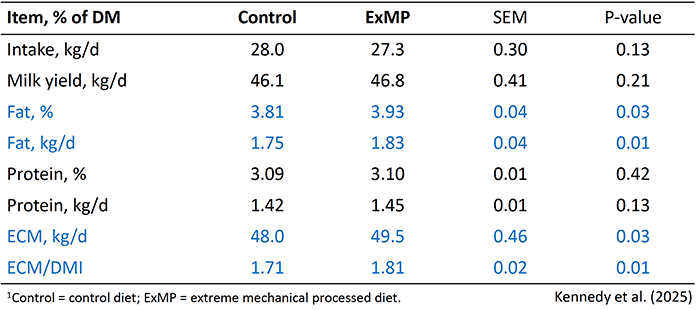

Kalscheur also showed results from a collaborative study between the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center and the University of Wisconsin on extreme mechanical processing (ExMP). This involves running forage through a hammer mill once its chopped, making silage particles thinner and exposing more stem material to rumen microbes.

Researchers compared rations containing conventionally chopped alfalfa and ExMP alfalfa; both diets were the same except for the forage processing. They found an almost 12% bump in NDF digestibility (NDFD) when cows ate ExMP alfalfa, jumping from 39.9% to 51.8% NDFD. Moreover, feed intake and milk production were stable, milkfat production went up, and thus, energy-corrected milk improved (Table 2).

“These are all things we are trying to achieve by feeding more silage in the diet to improve production,” Kalscheur said. Even so, the challenge lies in implementing advanced silage processing technologies like ExMP on-farm and making them accessible to farmers. “In this case, it’s still experimental, and these are questions we are addressing,” Kalscheur added.

Cover crop questions

To round out the presentation, Kalscheur shared two additional studies on alternative forage silages in dairy rations. As cover crops become more popular components of crop rotations — especially on Midwest farms — he noted that there may be opportunities to take advantage of their feed value in addition to the soil health benefits they provide.

“We are trying to improve soil health, we are trying to improve forage quality, and we are trying to improve the dairy cow ration. We are looking at that whole system,” Kalscheur said on behalf of the team of scientists at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center.

After analyzing the nutrient composition of four cover crop treatments, researchers found cereal rye, triticale, and three-way mixes of cereal rye or triticale with hairy vetch and camelina consistently had around 70% NDFD. Then, they replaced alfalfa silage in a control diet with the cover crop silages at rates of 15% for mid-lactation cows and 10% for cows in early lactation.

The preliminary results show feed intake did not change among the treatments in either experiment. Average milk yield was greater for cows fed cereal rye silage compared to their counterparts consuming triticale silage, although these cows produced more milk protein. Overall, Kalscheur confirmed cover crop silages can be fed at the rates demonstrated in the experiments; however, the research seemed to raise more questions than answers.

“Are there limitations if we have higher levels of NDF? Can we feed higher levels of some of these cover crops? Should we be concerned about some of the mixtures?” Kalscheur posited. Even though farmers have been incorporating cover crop silages into dairy rations for several years, he suggested more research is needed to help guide best practices and optimal inclusion rates.