Making quality hay is not for the weak of heart. In the arid West, there’s the challenge of baling with enough moisture in the final product. Head east, and the problem becomes getting hay to wilt to an acceptable moisture before the next rainfall event.

It’s this latter group that Dan Undersander spoke to at the Maryland-Delaware Virtual Forage Conference last month. The emeritus forage extension specialist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison explained to a large group of listeners that forage quality is the driving force behind livestock productivity and profitability.

When haymakers are on the fence between cutting hay with a known chance of rain or waiting out the inclement weather, Undersander usually recommends to cut, unless rain is a sure thing. “Whether you cut or not, forage quality is going to decline,” he noted. “In our studies, first-cut alfalfa neutral detergent fiber (NDF) usually increases by 0.4 percentage units per day and NDF digestibility declines by 0.4 percentage units. This translates to a loss of about 3.6 points per day in relative forage quality (RFQ).”

What drives drying?

Drying forage is no easy task. Plants contain about 75% moisture when they are cut. This means that 2 tons of cut forage per acre must lose 5.7 tons of water (1,374 gallons) per acre to dry to 13% moisture.

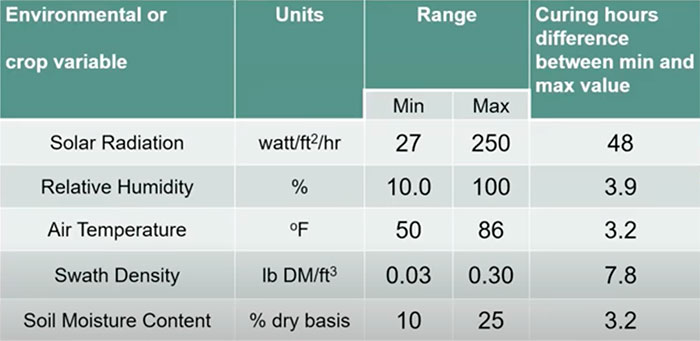

The factors that drive hay drying rate in the field are listed in the table below. “It’s easy to see that solar radiation is the single biggest factor that speeds drying,” Undersander said. “Air temperature and relative humidity are also important but much less so than swath density. The biggest single factor that farmers can control to speed hay drying is to spread out the swath.”

One of the primary goals for drying hay is to minimize the amount of plant respiration that occurs in the cut forage. Undersander explained that the breakdown and loss of sugars and starches during respiration translates to lost energy value and dry matter in the harvested forage.

This process continues in cut forage until the moisture content drops below 60%. “Dry matter losses as a result of plant respiration can range between 2% and 8%,” Undersander noted. “Even with a 4% loss, the economic impact is significant, approaching $50 per ton for alfalfa.”

Another factor that needs to be controlled is the development of molds and yeasts, which grow rapidly between 20% to 35% moisture. As with respiration, molds and yeasts consume valuable nutrients. They also result in heating, toxin development, and spore formation, which impacts both animal and human health.

Undersander recommends to cut alfalfa at 3 to 4 inches to improve quality and reduce ash content. This also leaves the swath elevated off the ground. Grasses need to be cut at 4 inches or higher to promote rapid regrowth.

Go wide

Returning to the benefits of a wide swath, Undersander noted that the relative humidity within a narrow windrow quickly climbs to near 100% and stays there for an extended period. As a result, little drying can occur below the windrow surface and respiration losses mount.

The benefit of a wide swath is that more sunlight is intercepted by the crop, taking advantage of the most important factor for rapid drying — solar radiation. Further, sunlight keeps the leaf stomates open and allows for water loss. The end result: Those first 15 percentage units of moisture are lost as quickly as possible.

Mowing in a wide swath that equates to at least 70% to 80% of the cutting width generally means some swath manipulation will be needed before baling. Undersander emphasized that any tedding, raking, or merging be done when moisture is still high enough to avoid substantial leaf loss.

“In many cases, it’s beneficial to ted cut grass hay about 24 hours after mowing,” Undersander said. “Grasses tend to create more of a flat mat after being cut compared to legumes.”

Ideally, the forage specialist suggested that raking or merging of alfalfa occur at a moisture content greater than 50%. “If you rake or merge at lower moisture levels, it’s best to wait until there is dew present and the forage is less prone to leaf loss,” Undersander noted.

How important are leaves?

Undersander said that the RFQ of alfalfa leaves is about 550. By contrast, stems are 70 to 80. “What we have seen in our studies is that leaf retention ultimately dictates forage quality. This is true for grasses or alfalfa.”

Even when everything is done to speed hay drying, sometimes Mother Nature just doesn’t cooperate. Cloudy days with high humidity are simply not going to be conducive for drying hay. Undersander pointed out that this is why many haymakers have shifted at least some of their production to baleage.

Forage quality is never better than the second it is cut. It’s unrealistic to think that we can stop dry matter and forage quality losses from cutting to baling, but the top-tier haymakers have learned how to minimize them in most situations.